THE LEGEND AND THE LORE

It was my original intent to write a book on the History of Southern Hillclimbing in hopes of capturing the feel of this wonderful event. I have been working on it for 8 years now. The more information I gathered, the more pictures I received and the more stories I heard… I began to realize that this is not a book one person can write. I decided instead to create this website, lay out the basic information how on the hillclimb was run and let you help tell the story. Memories of Chimney Rock is made up of stories from drivers, courseworkers and spectators that each have a unique story and experience at the greatest hillclimb in the south. Thank you for remembering and helping to build this website.

Editor of The Southern Driver – Ted Theodore

When you ask someone from the south about the roots of Southern Racing, you will undoubtedly be told countless stories of moonshiners that raced their work car on weekends. You will hear stories of dirt track racing, wheel to wheel with little safety equipment and little cash rewards. You will hear stories of men like Junior Johnson, Tiny Lund, Larry Pearson, Cale Yarborough and Ralph Earnhardt. These great men are legendary in their achievements and deserve the honor they are given today…but they are not all of the story of Southern Racing.

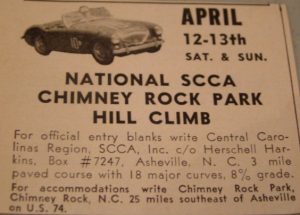

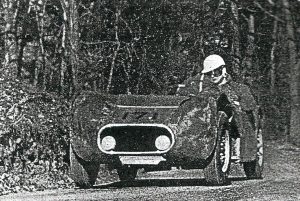

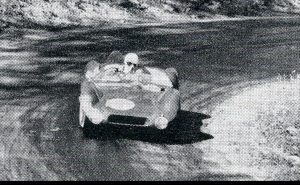

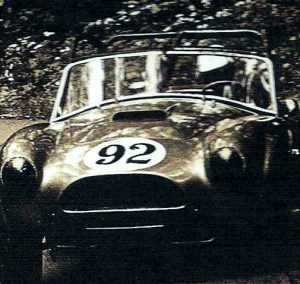

In the spring of 1956, a group of drivers raced from the foot of a mountain to the top of Chimney Rock one car at a time against the clock. The course was rough and dangerous, the cars were ill equipped for high speed mountain racing and many of the cars were brought down the mountain in pieces. The timing system was merely a horn at the start to notify the finish line to start a stop watch. The top prize was a brass trophy cup won by Phil Styles. The cars racing in the early years were not Fords, Oldsmobiles or Chevys or even Hudsons. They were mostly Austin Healeys, MGAs, earlyTriumphs. There were local names like Harold Butner, Dick MacIntosh and Jim Ray and they were know to take a practice run from time to time prior to the events. These men were students of European racing and knew time trials were a major step overseas in working your way up to Grand Prix racing. They were a part of the Sports Car Club of America and they began a tradition called the Chimney Rock Hillclimb. That spirit and tradition continued for 37 years and was the basis for some of the greatest sports car racing in the south.

This website is a record of one of the greatest hill climb events in the US. As you continue to read of the course, the drivers, the cars, the rivalries, the spectators and the story of the town of Chimney Rock, you will have a better understanding of what this race meant to so many and why it holds such an important place in racing history.

How the events were run

At 8:30, a drivers meeting was held to explain any changes in the track, potential new hazards since the year before, to explain run groups and to caution drivers of not trying to set a new record on their first lap. While the drivers were having their meeting, course workers were walking or being driven to their stations. Radios checked and all timing equipment inspected. Course workers insured spectators had great viewing opportunities for race watching and pictures but in a safe location.

At 9:00 the first group pulled to the line for a familiarization run. Drivers were already in their nomexs, with helmets, gloves and safety gear in place. The first driver would pull up to the line were the starter would place a chock under his rear wheel. When the radio signal came to the starter he would give the driver the signal to go. The driver would leave the starting line break the first timing lights beginning the clock for his run.

If the driver had a breakdown or went off course, he was given a DNF – Did Not Finish as his official time. If the driver had a breakdown and was unable to get his car to the line of to start, he was given a DNS – Did Not start for that run. When one driver was half way up the hill, the starter would signal the next driver to begin his run. It was vitally important that cars were spaced properly and that course workers were ready to red flag the next car if the one in front of it had an accident that could impede his run. When the car reached the top of the mountain, they would break a second timing light and their time for that run would be recorded and posted. Drivers would turn their cars around, park them and would wait until the run group finished. It was common for a driver to pull into the top , park his or her car in line and sprint over to the timing area to see what their official time was.

When all the cars in that run group had reached the top, the course marshals would allow the cars to come back down the mountain in groups of 4 or 5 in a parade lap. The drivers would wave and thank the course workers for making the event possible while the course workers applauded the drivers encouraging them to go faster and faster on each run. While the cars from that run group were coming down the mountain and back to their paddock area, the next group of drivers would be lining up for their runs at the mountain. With a break for lunch, run groups continued pending weather and delays due to car malfunctions or accidents. Sometimes the drivers were occasionally able to get two to three full runs at the mountain on Saturday and 4 to 5 on Sunday.

At 7:00 Sunday morning, the drivers were back in the paddock checking over their cars and looking at course maps. Each driver looking at their times and those of their competitors so they could find the precious seconds they needed to move to the top of their class.

By 5:00 the last runs were finished. Course workers were bused down the mountain and the awards ceremony was held. Spectators, drivers and workers applauded as each trophy was presented in class ending with the hillclimb special racers. Along with the class trophy, a special trophy was given for the King of the Hill, the fastest time of the weekend. That honor was held until the next year and during that year, drivers planned and worked to prepare for the next Chimney Rock Hillclimb.

THE IMPACT OF CHIMNEY ROCK

While many American racing fans followed early USAC and INDY racing, there was also a large body of people who were watching Grand Prix, the 24 Hour of Leman, and European racing. They loved the the smaller sporty cars, the wind in the face, the handling on road courses. These fans found a home with the Sports Car Club of America.

SCCA created a ruling body to sanction events so they could be held safely and fairly. The Chimney Rock Hill Climb was one of their finest events and drivers came from all over the US to compete. In the early days of Chimney Rock, many of the drivers were the “run what you brung” racers …cars that were not known for horsepower but for handling. That changed as the competition got tighter and tighter every year. The need to be the fastest in their class and for some, to be the King of the Hill, drove men to great extremes to build a car capable of accomplishing that goal. When they did, they experienced the thrill of the victory but when they lost, they had a year to and plan on how to get it next year. Many met their worst fear and had accidents that totally lost their cars. Some never returned while others came back the following year with another car and a stronger desire to win. These drivers pushed each other year after year to go faster, to set a new record. But they did it with honor and respect for each others skills and abilities. As drivers and as mechanics. A comraderie began that still exists in the sport of Southern Hillclimbing today.

The results of Chimney Rock Hillclimbs may well be defined as dreams. Young men saw a hill climb and vowed they would be there next year. Children watched and dreamed of the day they would run Chimney Rock. Old men watched with pleasure and imagined what it would be like. Women were inspired to see this was not only a man’s sport.The stories that came from Chimney Rock inspired people to race. Some stayed with hillclimbs while others pursued SCCA road racing or other forms of motorsport…but the base desire came from watching these men run up that mountain. It started dreams and that is the beginning of any great achievement. The point in time when you see it, and believe that you can do it and that you want to do it.

Chimney Rock inspired many people young and old to take up sports car racing. To build a car and compete. To develop their cars and skill sets to be the best and at the very least, the best they can be. In most forms of racing, records are frequently broken. This is the result of modern technology finding it’s way into the racing machine and giving modern drivers a decided edge over the old record makers of the past. With hillclimbing, records are NOT broken as often because beyond the technology, there is a skill set that takes years to develop.

We owe thanks to those who ran and worked the Chimney Rock Hillclimbs and appreciation to those who continue to aspire to make the mountains roar. Maybe, one day, we’ll make Chimney Rock roar again.